By: Andrew R. Halloran, Ph.D., Founder and Lead Consultant, The Elgin Center

Editor’s Note: Andrew R. Halloran, Ph.D., is a primatologist, conservationist, and animal welfare specialist with over 25 years of experience working with chimpanzees in sanctuaries, zoos, and the wild. This is the second in a three-part series by Halloran, first published by the Arcus Foundation, intended to raise awareness about the individuality of chimpanzees and the importance of the complex work done by sanctuaries and rehabilitation centers to care for them. A French translation is also available. Read Part 1, Burrito’s story and Part 3, Leo and Hercules’ story.

As the sun rises over Freetown Peninsula on the coast of Sierra Leone, a 1-year-old chimpanzee called Skippy awakens in a private enclosure in Tacugama Chimpanzee Sanctuary, located in 100 acres of national park forest outside Freetown, the nation’s bustling capital.

Today is special because Skippy is going to be introduced to a new group of chimpanzees within the sanctuary. As a rescued chimp, there are several phases of rehabilitation for Skippy, but today’s introductions are a significant milestone, not just for Skippy but for the sanctuary staff as well. These introductions are a sign of her health and strength, of overcoming the infections and malnourishment she experienced before her arrival.

It also begins the transition from humans providing her daily needs, toward Skippy relying on her chimp community for care, comfort, and companionship. Plus, she will be joined by two friends, Pitaya and Shine, who are in adjoining cages and roughly the same age as Skippy. They arrived around the same time as Skippy—and for all of them, this is a day for celebration, especially considering their history.

Why chimpanzee sanctuaries matter more than ever

To understand Skippy’s accomplishment, we must travel back 30 years to 1988, before Tacugama Chimpanzee Sanctuary (TCS) existed. Here is where we meet little Bruno, who helped inspire the formation of TCS. When TCS founders Bala and Sharmila Amarasekaran first met Bruno, he was sick and weak, tied to a tree in a small village. They paid $20 to rescue him, suspecting that if they didn’t try and help, he would soon die. As they nursed Bruno to health, Bala began working with wild chimpanzee researcher Rosalind Alp and found that there were 55 captive chimpanzees in Freetown alone. They also discovered that one of these chimps, whose name was Julie, had been abandoned by her owner. Soon after, baby Julie became part of the family.

Word spread that the Amarasekarans were caring for rescued and unwanted chimps, and as more chimps arrived, it became clear that Bruno, Julie, and the other orphans needed their own home. So, in 1995, Bala worked with the Sierra Leone government and international donors to set up Tacugama Chimpanzee Sanctuary in the Western Area Peninsula National Park.

Despite the success of Tacugama, the sadness lies in the need. Over the last three decades, the sanctuary has cared for over 200 chimpanzees from across Sierra Leone. And the story of how Skippy, Bruno, Julie, and other orphaned chimps arrived at the sanctuary have common threads. Most of these chimpanzees are infants when they arrive—the unfortunate by-product of chimpanzee poaching or human-wildlife conflict. In short, an adult chimpanzee is killed with a baby still clinging to her. The baby is taken alive and then sold as a pet.

Chimps are the national animal of Sierra Leone, but are still critically endangered

Thanks to the efforts of Tacugama Chimpanzee Sanctuary, chimpanzees are now the national animal of Sierra Leone and killing a chimpanzee carries stiff penalties. Yet despite these protections, chimpanzees are killed at an alarming rate within the country. In fact, according to some estimates, chimpanzee killings, along with devastating habitat loss, have contributed to a decline in western chimpanzee populations across West Africa by as much as 80 percent over the past 25 years. Why are so many chimpanzees being killed?

A key factor is human-wildlife conflict driven by, for example, farmers defending their crops. Deforestation is a serious concern, with Sierra Leone losing about 39 percent of its total tree cover from 2001–2024. Deforestation squeezes populations of chimpanzees into smaller and smaller forest fragments that cannot support an entire population. Being the resourceful species they are, chimpanzees find sustenance in adjacent farms. But for the human communities cultivating these crops, chimpanzees represent a major loss to what little they already have. Add to this the fact that chimpanzees are dangerous, have been known to harm livestock, and sometimes attack humans, and one can see why villagers killing chimpanzees is not surprising.

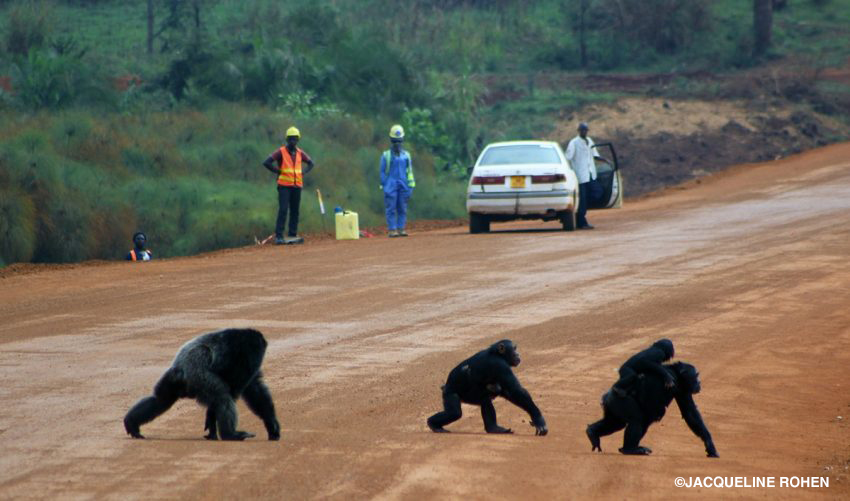

Other times, it is the reverse, with human activities encroaching on chimp habitats. For example, a foreign investor arrives and makes deals with local villages or regional governments to log in the remaining forest fragments. Soon come noisy chainsaws, backhoes, and large motors that echo throughout the land. Inside the fragment, chimpanzees react to the noise by moving quickly away from the sound.

But when they return, the contours of the fragment they had previously known have changed shape. They find themselves on a newly cleared road, having lost the protection of the forest. They are out in the open, exposed. And they can be sold for money: A single shot from a logger’s rifle brings down one of the chimps. The others run away. It is a female and clinging to her is her very much alive offspring—scared and now alone. The dead female can be sold for medicinal practices, ritual use, or bushmeat within Africa or the international black market. Meanwhile, the little chimpanzee is pried off his dead mother, bound with a rope, and tied to a truck until a small rusty cage can be obtained. He will be brought to a market in Freetown to be sold as a pet.

No one knows exactly how Skippy came to be orphaned and tied by her leg to a post in a Freetown market, for these scenarios are common. It has been repeated countless times. It will be repeated countless times in the future. What is definitively known is that Skippy was severely malnourished with infected rope burns around her leg when she was purchased at the market. She was intended to be a pet, but the buyer’s companion knew young Skippy needed more than they could provide, so eventually they took Skippy to TCS.

Despite a fragile beginning, Skippy is ready for her next adventure

As is the process for all new arrivals, Skippy was placed in a quarantine facility for 90 days. Most chimps that arrive at the sanctuary have suffered mistreatment, injury, infection, and some kind of mental trauma, and would normally be suckling milk from their mothers. Quarantine ensures the well-being of the new arrival—as well as the other residents—and allows them to be evaluated, monitored, inoculated, and assigned a specially trained staff member to care for them. Skippy was taken care of by a human foster mother named Mama P, one of two foster mothers at Tacugama who care for infants and juvenile chimpanzees as if they were their own. Their role is not just to feed and clean up after them, but also to provide the comfort and sense of safety these chimpanzees so desperately need during this frightening time. Mama P is known to sing to the young chimpanzees as she feeds and bathes them.

And now we have arrived at the last day of quarantine for Skippy and her friends. Pitaya and Shine vocalize at Skippy. She vocalizes back. Her behavior shows a mixture of both excitement and fear. Today, these three young orphans graduate.

All chimps at Tacugama go through this unique system of transition and rehabilitation: first the quarantine, then the nursery, then gradual integration with larger chimpanzee troops, and finally, access to a large forested area where they can choose to come to a feeding area and be fed by staff, or find their own food in the forest as a wild chimpanzee would. Each stage of graduation from one housing type to the next involves less and less human intervention and more and more bonding with their fellow residents.

As for Skippy and her friends, it is Skippy that begins the process. The door between herself, Pitaya, and Shine is opened, and Skippy is the first to step through. Within moments, they play. A bond is formed. Two years later, these three chimpanzees are still together—embarking together on a pathway to overcoming tragic events and finding a means to thrive.