Cliff Abenaitwe

Scientists have long wondered why people organize their relationships in layers: a few close friends, a bigger group of friends, and many acquaintances. This pattern, called Concentric Social Bonding Dynamics (CSBD), is seen as a key part of human social life.

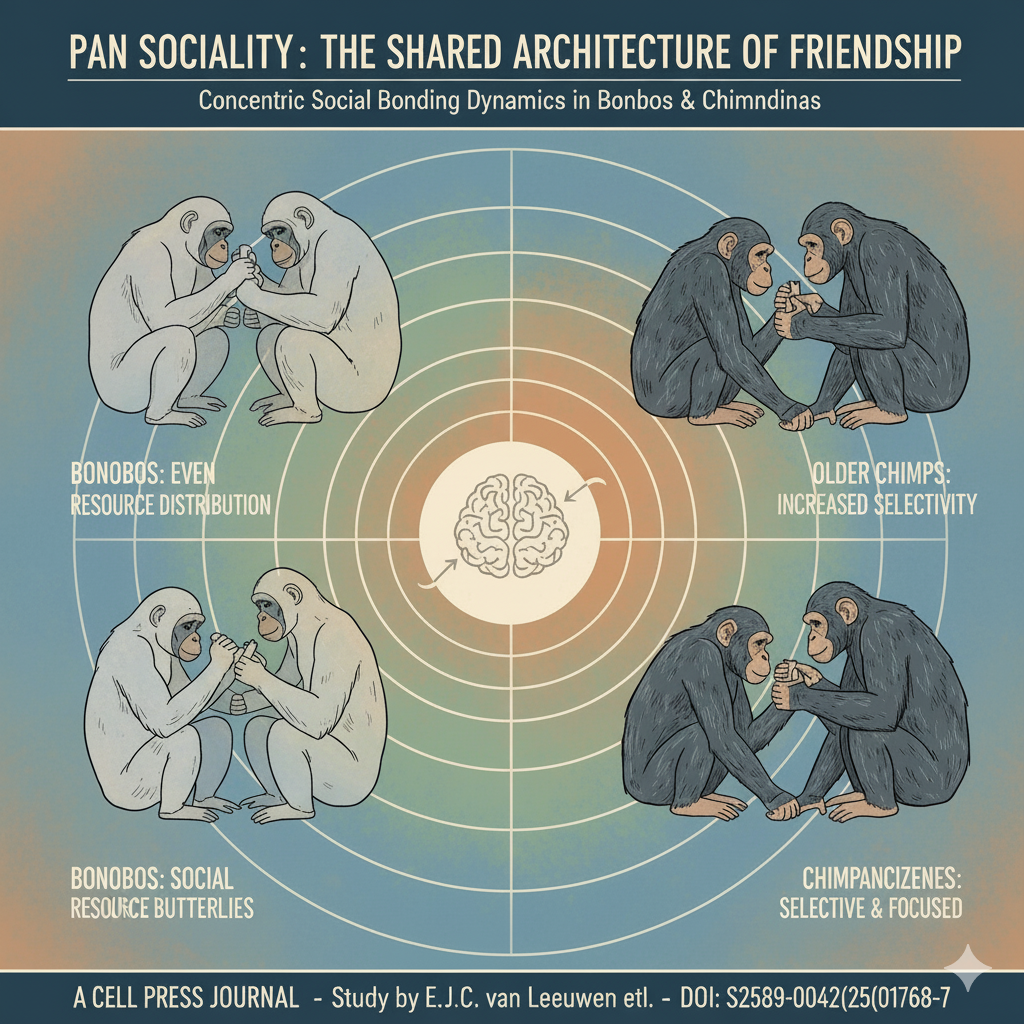

But what if this pattern isn’t just human? A new study, “The physics of sociality: Investigating patterns of social resource distribution among the Pan species,” suggests that these friendship rules are much older and also apply to our closest relatives, bonobos and chimpanzees. The research team was led by Edwin J.C. van Leeuwen.

The research, published in a Cell Press journal, looked at how these species share their most important social resource: allo-grooming, or mutual hair-cleaning. The goal was to see if they follow the same layered pattern as humans. The results show that the same basic social rules exist in primates, but each species has its own unique differences.

Study Findings: The Universal Social Budget

The main finding questions the idea that humans are unique. It suggests that this layered way of forming social bonds is an old pattern found in many complex species. It helps them manage limited resources like time, energy, and attention. Just like us, bonobos and chimpanzees have to decide how to share their social effort.

Both bonobos and chimpanzees share their grooming time unevenly, much like humans do with their friendships. They focus most on a few close partners and give less attention to others. The main reason for this pattern is the size of their social network. Those with more connections spread their effort even more unevenly, creating stronger layers in their social groups.

The study also found that bonobos and chimpanzees use different approaches. Bonobos spread their social attention more evenly, acting like social butterflies who connect with everyone. In contrast, chimpanzees are more selective, focusing their grooming on a smaller, more defined group. They act more like careful strategists.

Another discovery is the Age Factor: Adding another layer of human-like complexity, the The researchers also discovered an age effect. Older chimpanzees, but not bonobos, became more selective in their social bonds as they aged. Like older humans who focus on a few close relationships, older chimps also choose to spend time with fewer grooming partners. themselves socially in similar patterns as observed in human social networks.